Using Music in Public History:

Two Initiatves @ the Music of Asian America Research Center

Eric Hung & Mandi Magnuson-Hung

Music and Public History

Music is a powerful tool that can entertain, aid healing, and form community. It can also annoy, inflict pain, and divide peoples. Listening to a song is never a purely aesthetic experience. It is always informed by multiple contexts: the personal narratives of the artists, the cultures that they grew up in and encountered, the decisions made by industry representatives, the life experiences of listeners, and the socio-political circumstances at the time the song is consumed. To put it another way, a musical experience is always a historical experience that involves negotiating multiple strands of cultural, social, economic and personal memories.

Music is a powerful tool that can entertain, aid healing, and form community. It can also annoy, inflict pain, and divide peoples. Listening to a song is never a purely aesthetic experience. It is always informed by multiple contexts: the personal narratives of the artists, the cultures that they grew up in and encountered, the decisions made by industry representatives, the life experiences of listeners, and the socio-political circumstances at the time the song is consumed. To put it another way, a musical experience is always a historical experience that involves negotiating multiple strands of cultural, social, economic and personal memories.

Despite the fact that music reflects and can affect so many facets of societies and communities, it remains a largely segregated tool at museums and historic sites. To be sure, there are a good number of excellent music museums and music exhibits. At most public history institutions, however, music is an under-utilized resource.

On this page, we will show how music can be used to provide evidence that is not otherwise available, how it can help open difficult conversations, how it can demonstrate complicated concepts in visceral and convincing ways, and how music can help you build bridges across communities. We will first share two MAARC initiatives that use music to problematize, historicize, complicate and nuance mainstream narratives about immigration and the racial middle. Afterwards, there is a resource guide on how your museum, historic site or research center can use music to engage its visitors.

On this page, we will show how music can be used to provide evidence that is not otherwise available, how it can help open difficult conversations, how it can demonstrate complicated concepts in visceral and convincing ways, and how music can help you build bridges across communities. We will first share two MAARC initiatives that use music to problematize, historicize, complicate and nuance mainstream narratives about immigration and the racial middle. Afterwards, there is a resource guide on how your museum, historic site or research center can use music to engage its visitors.

About the Music of Asian America Research Center

The Music of Asian America Research Center (MAARC) strives to increase knowledge and awareness of Asian American history and experience through collecting and conducting research on materials related to music-making by Asian Americans, and disseminating information and opening difficult conversations raised by these practices. Our current work includes the podcast and “Documenting Asian American Community Music Ensembles” initiatives (both discussed below), a biographical dictionary of and Wikipedia entries on Asian American composers of Western classical music, a textbook on the social history of Asian American music, and co-sponsoring or appearing at selected community events and academic conferences.

MAARC’s Podcast Initiatives

In 2020, MAARC is releasing two podcast series. Each uses music and musicians to draw out the diversity of Asian American experiences and to show how Asian Americans have tried to both pass on and reject elements of their cultural heritage. We also use their words and creations to uncover how the logic of exclusion underlies much of Asian American history and how they interact with their surroundings.

Bringing Up Music

In “Bringing Up Music”–which we will begin to release in April–Asian American musicians tell their own stories, and discuss everything from their early life and musical experiences to aesthetic philosophies, and from their initial impressions of the United States to problems faced by their ethnic communities. Interspersed with excerpts from oral histories, each episode analyzes a piece of music created by the interviewee.

In “Bringing Up Music”–which we will begin to release in April–Asian American musicians tell their own stories, and discuss everything from their early life and musical experiences to aesthetic philosophies, and from their initial impressions of the United States to problems faced by their ethnic communities. Interspersed with excerpts from oral histories, each episode analyzes a piece of music created by the interviewee.

In making this series, we aim to demonstrate not just the diversity of Asian American experiences, but also the different ways these musicians deal with similar issues arising from the dominant racial structure of the United States.

Below are excerpts from three episodes that demonstrate how music and musicians might be useful to public history institutions that are interested in discussing race, immigration, diasporas, and community building.

In the first episode, Chinese American rapper Jason Chu discusses his song “This is Asian America” (video by Michael Tow and Teja Arboleda), which will serve as the theme song for the podcast series. This song juxtaposes the model minority stereotype (along with the call for moderation that is common among newer immigrants) with the anger in our communities. It also brings to the fore the issue as cultural appropriation; can and how can a Chinese American who grew up in the suburbs of Wilmington, Delaware appropriately perform rap? Finally, the song–which is very obviously inspired by Childish Gambino–can open conversations about what creativity is and the stereotype of the uncreative Asian nerd.

In another episode, Vietnamese American composer and multi-instrumentalist Van Anh Vo discusses her first visit to the United States as a visiting performer in 1995 and how she began re-establishing herself as a professional musician after she moved to the San Francisco Bay area in 2001. In this excerpt, she talks about her introduction to the politics and food culture of the Vietnamese American community, and her first impressions of San Francisco.

We believe that public history institutions can use musician oral histories like these to talk about the experiences of refugee communities, the roles that music and art can play, the relationship between homelands and diasporas, and so on. This episode also examines an analysis of Vo’s 2012 composition Three-Mountain Pass, which can be used to discuss how immigrants combine elements of homeland and American cultures. Here is a complete recording of the work; if you want to watch her perform, Vo performs an excerpt of this work at the beginning of her NPR Tiny Desk Concert). Based on the four-couplet poem by 19th-century Vietnamese woman poet Ho Xuan Huong, the song initially invites readers to explore the beautiful landscapes. By the third couplet, however, it becomes clear that this scenery is also a metaphor for human bodies, and that the poem is also inviting us to explore human sexuality. To portray this sensual and erotic text, Vo combines modernist techniques from the Western classicla tradition with Vietnamese sung poetry and Vietnamese trance singing—musical practices that allow her voice to go from a whisper to a scream, and from gentle to steely.

In a later episode in the first season, we will hear how technologist and tabla player Ajay Dholakia builds bridges across communities. In this excerpt, he discusses his collaboration with a turntablist.

Here is Ajay Dholakia and Jay Parker performing a tabla-turntable duet:

For us, what is important about this clip is not just that there are similarities between the sounds and traditions of the tabla and the turntable, but also that they retain their differences. The world would be a much less interesting place if everything is just fused together.

We hope that these examples encourage you to look at music and musicians as an important resource for your public history institution. We believe that these materials can enhance your exhibits, enable you to engage more deeply with your audiences, and enhance your institution’s ability to help build community.

To subscribe to this series, please come back to this page or look for “Bringing Up Music” in your favorite podcast app in late April.

Who Is An Immigrant?

In “Who Is An Immigrant?” (a seven-episode series), we complicate metanarratives about immigration that focus on choice, assimilation and the notion of Asians as “model minorities.” We are interested in exploring how we should tell the (im)migration stories of:

In “Who Is An Immigrant?” (a seven-episode series), we complicate metanarratives about immigration that focus on choice, assimilation and the notion of Asians as “model minorities.” We are interested in exploring how we should tell the (im)migration stories of:

- 19th-century/early-20th-century Chinese workers who stayed in the US only because they could not afford a return ticket

- Asians who came to the U.S. when the government did not grant citizenship to people who are not white

- Filipinos who came to the United States as U.S. nationals when the Philippines was an American colony, and as members of U.S. Armed Forces.

- Southeast Asian refugees who were relocated to the U.S. since the 1970s.

- Adoptees from South Korea, Vietnam, China, India, and other countries who had no choice whatsoever in moving in the U.S.

Through this series, we hope to show the diversity of Asian American communities and to open conversations about the manifold reasons Asians come to the United States. We also desire to subvert the “model minority” myth (and the anti-blackness on which it is predicated), which willfully ignores the real factors affecting educational and financial success, and keeps Asians both docile and perpetually foreign.

Each episode of “Who Is An Immigrant?” begins with an analysis of one or two songs that discusses a type of migration that does not quite fit the traditional metanarrative, and continues with conversations with one or two scholars who specialize on this topic. It is scheduled for release in time for the Fall 2020 semester. Here are previews of the musical segments of two episodes.

In the opening episode about the 19th-century Chinese workers, one of the works we examine is Jon Jang’s Chinese American Symphony (2007). Here is an excerpt of this 24-minute work:

In this interview with Eric Hung and Byron Au Yong, Jang discusses why he used the anvil so prominently in this composition.

Discussing this work allows us to discuss the achievements of Chinese railroad workers. Through interpreting Jang’s music, we can also open conversations about the different ways we can tell the stories of these (im)migrants, the continuing relevance of their experiences in the 20th century and today, and the role of race can play in capitalist societies.

In the episode of Southeast Asian refugees, we analyze these two songs. The first is by the pioneering Cambodian American rapper praCh Ly (as a performer, he goes by “praCh”). In “The Art of FaCt” from his second album–Dalama: The Lost Chapter (2003)–he tells us about his background as a refugee, but also that many in his community are continuing to struggle in the United States. In his Cambodian mecca of Long Beach, California, generations cannot communicate with each other, and numerous people are suffering from deep depression and PTSD. The community is also threatened by gang violence–for many Cambodian American youths in the 1980s and 1990s, gangs offered community, protection and jobs–which also led (and continues to lead to) INS/ICE deportations based on “one strike and you’re out” immigration policies.

In the original recording of this song (which is not available online), the backing track opens with a digitally manipulated Cambodian flute (khloy), and morphs into a fusion of R&B and traditional Cambodian court music (pin peat). It signifies not just the inbetweenness of Cambodian American society, but also the fact that praCh, who is bilingual, sees himself as a “bridge” between generations. He will listen to his parents’ stories “without interference,” and communicate them to those who are younger.

In the following song, Bochan Huy (she goes by Bochan as a performer) also uses fusion–in this case, a famous early 1970s Cambodian psychedelic rock song and a more contemporary American R&B vocabulary–to get her community to move beyond its sense of exile nostalgia and to build towards a brighter future.

DAACME Initiative

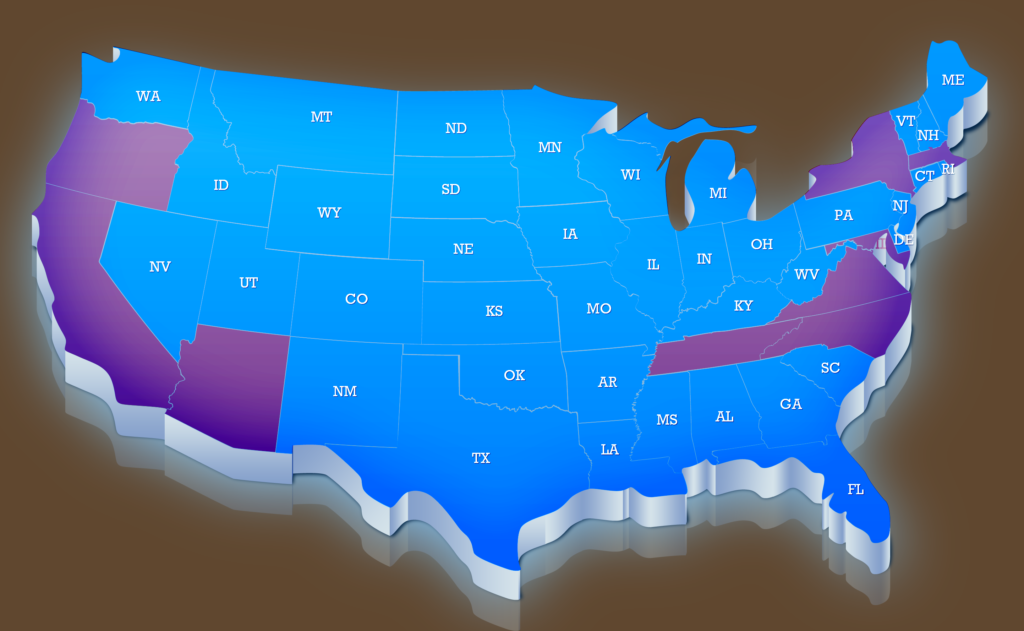

We have begun working with ensembles in OR, CA, AZ, MA, NY, MD, VA and NC.

The “Documenting Asian American Community Music Ensembles” initiative is a four-year project that aims to chronicle the activities of at least 70 groups in thirty states. Currently eight months into this project, we have begun to work with ensembles in eight states (see map to the right). They play a wide variety of music, from traditional music to punk, and from jazz to hip hop.

The main goals of this project are:

- To help our audiences understand the many ways that Asian Americans have used music (e.g., for entertainment, to assimilate, to gain cultural capital, to preserve preserve ancestral cultures, to fight for social change and justice, to reject elements of homeland cultures)

- To increase visibility for groups that we document and, more generally, for Asian American community music ensembles

- To produce resources and connections for educators who are interested in teaching Asian American history and experiences

- To publish materials (e.g., oral histories, archival materials) for researchers who are studying Asian American music.

- To help community ensembles archive their own materials better.

We are beginning to create webpages for each of the participating bands. Below, you will find links to three of the pages we have started.

Awaaz Do

The brainchild of Saraswathi Jones, Awaaz Do (“Make Some Noise”) is a Boston-based South Asian American punk band. They simultaneously foster elements of traditional South Asian cultures through presenting chants, prayers and Bollywood songs with a twist, and fight traditional beliefs that cause oppression, such as caste discrimination and sexism. The band members have distinctive approaches to music-making. Jones believes that their music can and should be radical. She thinks deeply about how she can use music to make the world a better place. Meanwhile, guitarist Jagdeep Singh is primarily interested in musical explorations when he plays with the band, and tabla/dhol player Chhavi Goenka uses her activities in the band to affirm her South Asian American identity.

Greater Boston Chinese Cultural Association Chinese Music Ensembles

Originally a part of the Chinese Students Club at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, this organization became a part of the GBCCA in 1984. Based in Weston (1984 to 1993) and West Newton (since 1993), the GBCCA Chinese Music Ensemble was the first Chinese community ensemble in the Boston region outside Chinatown. Its long-time Executive Director, Tai-Chun Pan–a Chinese flute (dizi) player and a tai chi instructor–has played in the ensemble since 1980. He attributes the continuing success of the group largely to family connections (there are many parent-child and siblings combinations) and to the fact that many ensemble members have become good friends. Today, this organization includes an adult ensemble, a youth ensemble, and a percussion ensemble.

SNRG

S.N.R.G. (Some Never Really Get [___] #FEELintheBLANK) is a Filipino American songwriting duo based in northern Virginia. Beau “L.A.S.T.O.N.E.” and Aaron “eyespk” Canlas, the “Super Barrio Brothers,” see their name as an invitation–an invitation for you to fill in the blank and “let everyone know what Some Never Really Get about you.” They believe that, although we can never really truly understand each other, we should try to connect. The two brothers grew up in northern Virginia, but they spent much of the last six years in their ancestral homeland in Pampanga province, located about 45 minutes north of Manila, writing many songs about lost love. Today, they are working hard to build an inclusive community of independent artists, largely through their monthly artist showcases at Jammin’ Java.

Resource Guide for Using Music in Public History

Below, you will find links to and short annotations of resources we find useful. In compiling this list, we have included books, but have avoided articles that are behind paywalls.

We have organized these resources into four categories: finding historical evidence in music, using music in programs and tours to open difficult conversations, using music in curatorial practice to demonstrate complicated concepts in visceral and convincing ways, and using music to build bridges across communities. Several of these resources can go into multiple categories. If you are interested in discussing these resources with us or if you want to find additional materials, please email us at info [at] asianamericanmusic [dot] org.

Finding Historical Evidence in Music and the Lives of Musicians

Books:

How Early America Sounded by Richard C. Rath (2003): In this volume, Rath examined how European American, Native Americans and African Americans from 1660 to 1770 interpreted and often made key decisions based on the sounds they heard.

Sounds of Slavery Discovering African American History through Songs, Sermons, and Speech by Shane White and Graham White (2005): This volume identifies the sounds that those who were enslaved made and heard, and tries to understand what they meant to both African Americans and whites. The authors ultimately argue that, for slaves, sound often represented a temporary refuge–a place where they can retain a bit of their identities.

Sonic Color Line: Race & the Cultural Politics of Listening by Jennifer Lynn Stoever (2016): Examining the period from the mid-19th century to the mid-20th century, Stoever argues that sound and listening practices not only reflect, but also help to create and enforce the racial hierarchies of the United States.

The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967 by Amy Abscher (2014): This volume explores how musicians who resided in Chicago’s South Side navigated the racial politics of this highly segregated city to make a living.

Digital Projects:

The Roaring Twenties by Emily Thompson and designed by Scott Mahoy: This site is an interactive exploration of the historical soundscape of New York City through archival material—primarily noise complaints.

London Sound Survey by Ian Rawes: This is a growing collection of recordings of life in London presented with historical recordings from the 1920s-50s.

Engaging Visitors by Having Them Look for Historical Evidence in Music:

Music of the Civil War: This extensive resource explores music’s role in the American Civil War through objects, recordings, and photographs in this resource from the Kennedy Center.

Switched on Pop with Nate Sloan and Charlie Harding: Each episode of this podcast focuses on a single artist and puts their work into larger cultural and historical contexts. The hosts are great at delving into complicated music theory concepts without resorting to any jargon.

What Can Songs Tell Us about People and Society? by Ronald G. Walters and John Spitzer for the History Matters, a collaborative project created by American Social History Project, the Center for Media and Learning (Graduate Center, CUNY), and the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (George Mason University): This curriculum examines the ways music and songs can be used as primary sources.

The Sounds of Change: This is a curriculum offered by the Facing History and Ourselves and written by staff from the Stax Museum of American Soul Music. Lessons such as “Soul Man and Identity,” “Breaking the Racial Barriers.” “Respecting Yourself and Others,” and “Race in US History” explore the way American society and soul music relate to and comment on one another.

Music Lyrics: Engaging Primary Resources: In this piece written by Ed Casey for National Geographic’s Education Blog, you can learn how you can approach understanding apartheid with music.

11 Classic Hip-Hop Songs You Can Teach With: Terry Heick offers 11 songs with short descriptions and suggestions for connecting them to Common Core requirements.

Using Music in Programs and Tours to Open Difficult Conversations

Books/Article:

Contemporary Music Tourism: A Theory of Musical Topophilia by Lionieke Bolderman (2020): Based on ethnographic studies of musical tourism in Europe, this volume examines how people create and celebrate affective attachments to places through and with music.

Performing Nashville: Music Tourism and Country Music’s Main Street by Robert W. Fry (2017): This book explores Nashville’s multifaceted musical identity, and how tourists come to the city to experience–through country music–an idealized and nostalgic American identity.

The Jazz Bubble Neoclassical Jazz in Neoliberal Culture by Dale Chapman (2018): Chapman argues that, starting in the 1970s, corporate interests began to co-opt the “riskiness” and “living-in-the-moment” nature of jazz in their business strategies, and to see the music as a “site of urban philanthropy.”

Music and Anti-Racism: Musicians’ Involvement in Anti-Racist Spaces by Anna Rastas and Elina Seye (2018): This ethnographic study examines how Finnish musicians negotiate race and anti-racism activities in their work.

Digital Projects:

Lemonade Syllabus: Inspired by Beyoncé’s album Lemonade, Candace Benbow initiated and crowdsourced this syllabus with over 250 sources about the lives of black women.

Not Another Music History Cliché: Created by the late Linda Shaver-Gleason to be the classical music version of Snopes, this blog shows how music historians have often worked to promote composers and compositions as “masters” and “masterworks” at the expense of erasing what is most interesting and historically accurate.

Methodological Discussions:

Teaching Don Giovanni at Eastern Correctional Facility: original article by Pierpaolo Polzonetti, with responses by William Cheng and Bonnie Gordon (2016): These three articles explore the opportunities, perils and ethics of using music to teach in broader contexts. It reveals how every genre or even every piece of music carries assumptions about race, gender, class and abilities.

These Women Are Giving Voice to a Prison Sentence: Interfaith Prison Ministries for Women volunteer Susanna Long started a songwriting workshop at the North Carolina Correctional Institution for Women. In this interview from North Carolina Public Radio, Long and Luverta Gilchrist and Loyane Propst, two former inmates and songwriters, talk about their relationships with music. Click here to listen to IPM for Women’s 2017 Convictions concert.

‘Killing Me Softly’ with His Song: Exploring Racism in Football Chants, Media Literacy Module and Journalism Training Unit by Jamie Fowlie and Phil Mac Giollan Bhain: This module presents a number of case studies involving racism in football along with how the media responded at the time. It includes activities that utilize critical reading and thinking techniques and tips for the difficult task of talking about race.

Using Music in Curatorial Practice to Demonstrate Complicated Concepts in Visceral and Convincing Ways

Books/Thesis/Article:

Curating Pop: Exhibiting Popular Music in the Museum by Lauren Istvandity and Raphaël Nowak (2019): Based on interviews with curators in the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Europe, Istvandity and Nowak examine how popular music is presented to visitors of music museums around the world.

Preserving Popular Music Heritage: Do-it-Yourself, Do-it-Together edited by Sarah Baker (2019): This essay collection examines community archiving of music heritage around the world. It explores different approaches to collecting and providing access, and various ways to collaborate with professional institutions.

Sites of Popular Music Heritage: Memories, Histories, Places edited by Sara Cohen, Robert Knifton, Marion Leonard and Les Roberts (2014): This essay collection explores the location (broadly defined) of popular music memories and histories. Among the locations discussed are cities/regions, archives, nostalgic sites, and pilgrimage sites.

Does Music Matter to Museums: Understanding the Effect of Music in an Exhibit on the Visitor Experience by Briana Brenner (2016): In this master’s thesis, Brenner discusses an experiential study she conducted at the Renton History Museum. For our purposes, her key finding is that visitors who went through the exhibit with music learned more than visitors who did not hear music.

Music for Spaces: Music for Space–An Argument for Sound as a Component of Museum Experience by Tim Boon (2014): Reflecting on the London Science Museum’s Apollo Moon Landings celebration in 2009–an event that included a performance of Brian Eno’s Apollo album–Boon argues that sound can transform not only spaces, but also historical thinking.

Curated Projects:

Trax on the Trail: This project, founded by Dana Gorzelany-Mostak at Georgia College, shows the power that music and sound have in American presidential campaigns and in forming candidate identity.

Biorhythm: Music and the Body, The Health Museum, Houston, Texas: This exhibit, designed by Science Gallery Dublin, explored the scientific reasons why we dance, what happens in our brains when we listen to music, and provided opportunities for hands-on engagement.

Hamilton: The Exhibition, Northerly Island Chicago: No one can deny the cultural power of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, and now there’s a new blockbuster museum exhibit as well, complete with 3D video, sound, interactive games, and “Instagram-worthy” art exhibits. How do we take academic history and put it on stage and then return that history to the academy?

Star-Spangled Music: This website uncovers the largely forgotten history of patriotic music in the United States. The foundation also supported recordings of interesting versions of patriotic songs, created a traveling exhibit, and published curricular materials.

Jane Austen: At Home With Music, Sydney Living Museums: Jane Austen’s hand-written music albums offer a new perspective on her work as well as the importance of music making in the era.

The Art of Rock: Four Museums Explore How We Connect to Music, New York Times: Critic Mark Richardson reviews four exhibits centering pop music and musicians at the Jewish Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Arts and Design, and the Museum of Sex.

Methodologies:

Art from Start to Finish: Jazz, Painting, Writing and Other Improvisations edited by Howard S. Becker, Rober R. Faulkner, and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett: We usually concern ourselves with the finished product when it comes to art. The Contributors to Art From Start to Finish explore the creative process itself.

Using Music to Build Bridges Across Communities

Books:

The Routledge Companion to the Study of Local Musicking edited by Suzel A. Riley and Katherine Brucher (2018): This reference book explores how different people around the world engages with community and place through music.

The Oxford Handbook of Community Music edited by Brydie-Leigh Bartleet and Lee Higgins (2018): This is the “go-to” book on the field of community music. It is more theoretical and future-looking than the Routledge Companion above.

What I Found in a Thousand Towns: A Traveling Musician’s Guide to Rebuilding America’s Communities—One Coffee Shop, Dog Run, and Open-mike Night at a Time by Dar Williams (2017). This book draws on the singer-songwriter’s personal experiences and the work of urban theorists to propose solutions to declining communities. Music is one of several strategies offered. Several of her suggestions can be adapted for public history settings.

Performing Ethnomusicology: Teaching and Representation in World Music Ensembles edited by Ted Solis (2004). This essay collection focuses on the academic world music ensembles. Many chapters are relevant to museums who are interested in experiential learning and in bringing in world music ensembles for their programming.

Sonic agency: Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance by Brandon LaBelle (2018). This book asks whether sound and listening can serve as the basis for social change.

Projects:

Healing and Connecting Across Generations at the National Cambodian Heritage Museum: This article discusses the role that music and dance classes (along with an exhibit and ritual) give young Cambodian Americans in Chicago pleasure, learn the cultural heritage, and help them deal with trauma, and intergenerational conflict and misunderstandings.

Earth Voices: Exploring Our Identity Through Choral Music Singing and Visual Art, developed by Dr. Andrea McComb, Christine Lafond, and Diana Clark: This curriculum guide shows how First Nations’ Principles of Learning can be incorporated in a music curriculum. It is useful to museums how are trying to learn how indigenous epistemologies can influence their programs and exhibits.

Musicians Without Borders: Established in May 1999 by founder and director Laura Hassler, and registered as a charitable foundation in 2000, Musicians Without Borders is the world’s pioneer in using music for peacebuilding and social change.

Invisible in Prison, Mandela was Kept in Spotlight by Music, Marius Bosch for Reuters: Nelson Mandela was incarcerated for 27 years, but his memory and the “Free Nelson Mandela” movement were kept alive by musicians and their songs.