From 1790 to 1952, the United States enforced a racial requirement for naturalization. Until 1870, naturalization was restricted to “free white persons.” Then, in the next 82 years, naturalization was open to “free white persons” and “aliens of African nativity and persons of African descent.” This language was oddly confusing: some people were eligible because of a color, but others were eligible because their ancestors were from a particular continent. Some argued that, if Congress wanted to define “White persons” as people of European descent, it would have stated that clearly in the law. This language ambiguity led to three key Supreme Court decisions in the early 1920s.

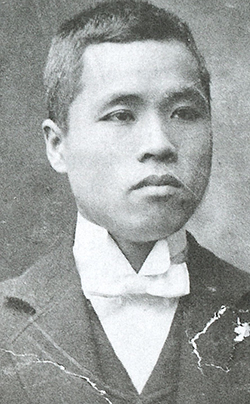

November 13, 2022 marks the 100-year commemoration of the Takao Ozawa decision. In this unanimous ruling, the United States Supreme Court ruled that Ozawa was ruled ineligible for naturalization. Delivered by Justice George Sutherland, the Court ruled that “the words ‘white person’ were meant to indicate only a person of what is popularly known as the Caucasian race.” The justices recognized that there will be “border cases” in racial classification. However, they decided that, because Japanese people are not considered Caucasian in ordinary usage, then they do not fit the definition of “free white persons” under the 1906 Naturalization Law.

In many Western and Midwestern states, there were, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, “alien land laws” that barred “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning land. In 1922, an activist named Takuji Yamashita decided to challenge Washington State’s alien land law. The success of this challenge ultimately rested on Yamashita’s ability to naturalize. In its decision, which was handed down on November 22, 1922, the court ruled that the Washington law was constitutional, and cited the Ozawa decision they delivered nine days earlier.

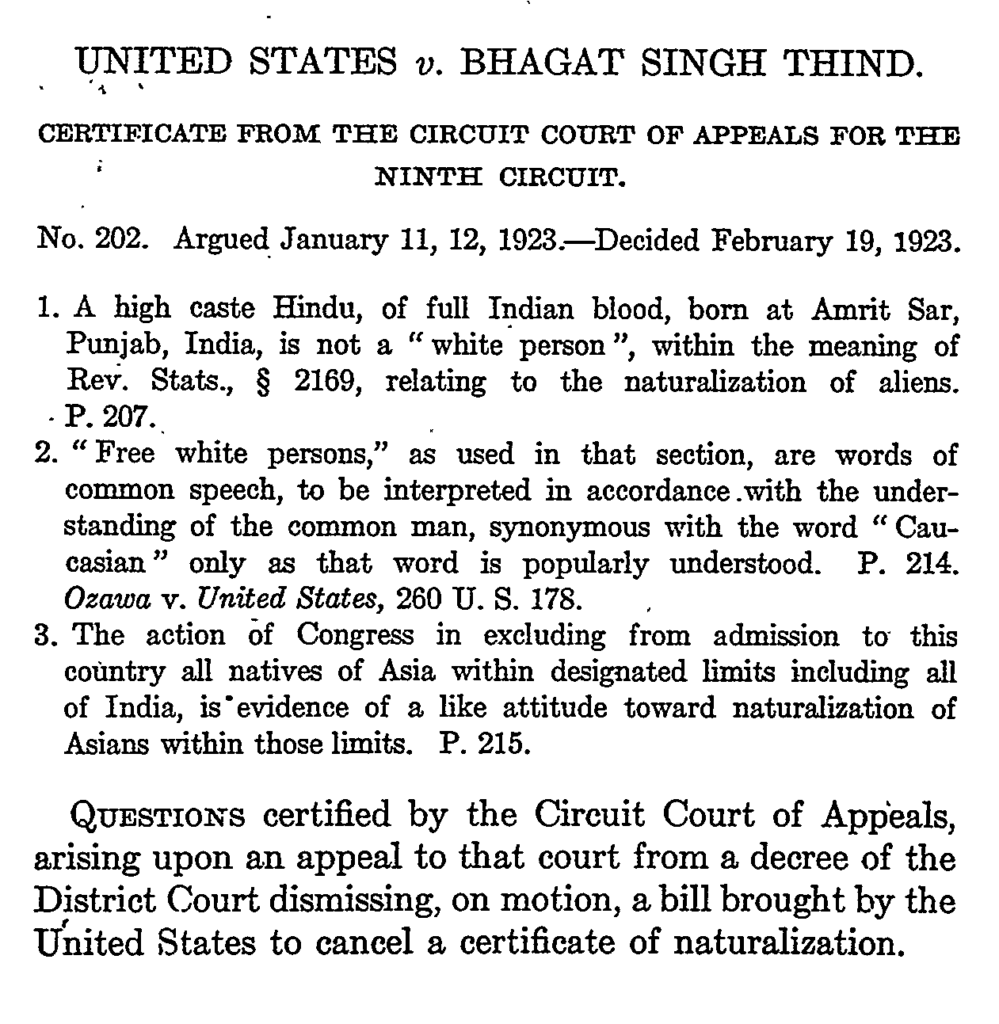

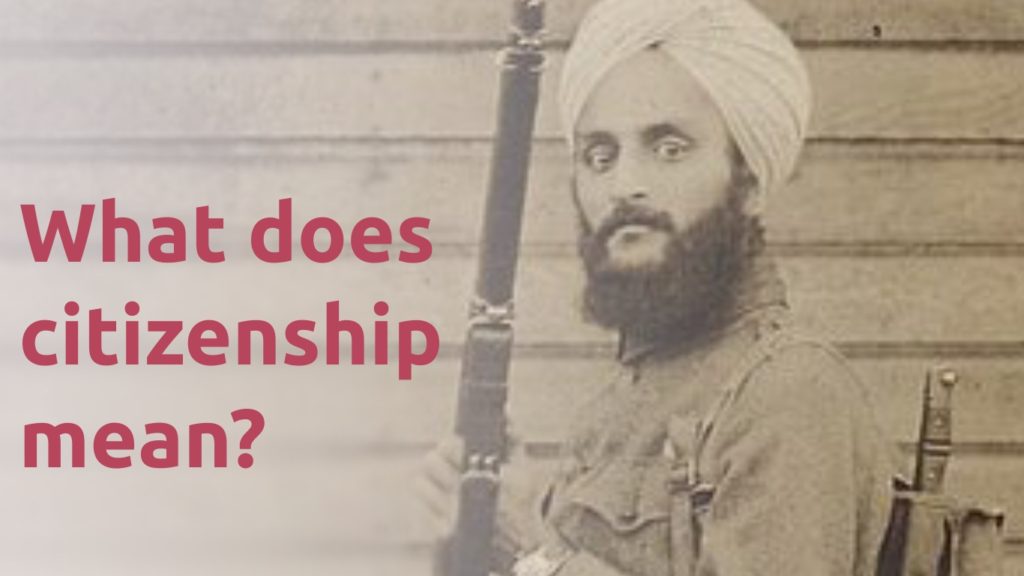

February 19, 2023 marks the 100-year commemoration of the Bhagat Singh Thind decision. In that unanimous ruling, the United States Supreme Court argued that Thind could not be a naturalized U.S. citizen because he did not fit the “common sense” and “popular” understanding of Whiteness. This ruling led to the denaturalization of approximately 64 Americans of South Asian descent, and the departure of many South Asian families who were living in the United States. When businessman Vaishno Das Bagai lost his citizenship, he suddenly became subject to California’s discriminatory 1913 Alien Land Law, which forbade “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning or long-term leasing certain types of property. He was forced to sell his business, Bagai’s Bazzar, and was ultimately driven to commit suicide in 1928. These three decisions showed the limits of Asians’ claim to Whiteness. They also further ignited anti-Asian sentiments, which led to the passage of the highly restrictive 1924 Asian Exclusion Act.